Threats of Regulatory Arbitrage from Differential Implementation

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN REGULATORS WORLDWIDE HAVE BEEN EVOLVING FOR A LONG TIME, EVEN BEFORE THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS THAT PROMPTED FRTB

- FRTB rules will involve an increasingly complex burden for national supervisors, which could be made even more challenging by the threat of regulatory arbitrage

- This risk is fully acknowledged by the Basel Committee, but doing something about it is not straightforward

- Differing frameworks for implementation the rules are already emerging, and it is inevitable that local supervisors will take into account local market factors when framing their rules

- National interests may be perceived to be under threat from the detailed rules of FRTB, especially in the context of a more widespread rollback of globally imposed regulation

- A high degree of harmonization will need to be achieved, difficult though that is, if the FRTB is to fulfill its destiny as a fundamental solution to a global problem

A change in the supervisory paradigm

As befits its name, the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) involves a fundamental change in the paradigm for the regulation and supervision of trading banks. For example, given the new emphasis on Regulatory Trading Desks (RTDs), the relationship between supervisors and banks will involve much more direct interaction with RTD head traders, who will need to develop a granular framework and tools for reporting and compliance with the new supervisory rules on oversight of their operations.

These challenges are caused partly by the prescriptive nature of FRTB, yet even within this highly prescriptive framework, there can be ambiguity in interpretation, differences in jurisdictional rigor, and potential arbitrage across geographies. Furthermore, the increased burden placed upon supervisors around the world by FRTB will be substantial. Supervisors will be asked to approve increasingly complex models, methodologies, and calculations at a more granular level than before, often within tight timeframes. Consequently, supervisors will need to implement new technologies to facilitate oversight or risk falling behind the institutions they supervise. Regulators will also increasingly need to harmonize their methodologies across and within jurisdictions, or face the prospect of regulatory arbitrage perpetrated by aggressive, well-funded financial institutions.

Better co-ordination needed between home and host country supervisors

Coordination of home and host supervisory authorities under different jurisdictions will be increasingly important under FRTB, due to the granularity of supervision needed at the RTD level. FRTB acknowledges explicitly that:

Home and host country supervisory authorities of banks that carry out material trading activities in multiple jurisdictions intend to work cooperatively to ensure an efficient approval process. (FRTB Final Rules, January 2016, para 176)

Yet there is significant potential for regulatory arbitrage as well as jurisdictional capital flight if FRTB implementation is not implemented harmoniously across jurisdictions.

Possible areas of tension between home and host country regulators will fall into three broad categories: (i) differences in rules implementation; (ii) differences in market dynamics; and (iii) disjointed approval processes for global banks operating under multiple jurisdictions.

(i) Implementation of the rules

We are already witnessing differences in FRTB implementation across jurisdictions. For example, the European Commission has proposed rules for phasing FRTB in over a three-year period, starting in 2019, and has passed key tests, such as P&L attribution, over to the European Banking Authority (EBA) for further study. Meanwhile in the US the Federal Reserve Board has yet to issue a notice of proposed rulemaking, while in Australia APRA is advising affected Authorised Depository Institutions that it does not envisage a new market risk standard being finalized until the beginning of 2020 at the earliest.

If, as many argue, capital flows increasingly like water across global jurisdictional boundaries to its most productive venue, then asynchronous implementation of FRTB in different locations will inevitably cause realignments in capital formation across jurisdictions. When considering how far to stray from FRTB’s prescriptions, regulators will need to be increasingly aware of the trade-offs between regional dynamics and global capital drivers.

(ii) Market dynamics

We know that FRTB will impact jurisdictions asymmetrically. For example, with its emphasis on liquidity horizons, FRTB will have a disproportionately large impact on less liquid markets such as Asia, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe, compared to highly liquid markets in North America and Europe. Jurisdictions that support their housing, automotive, or consumer sectors through securitization will be disproportionately impacted by FRTB’s disallowance of IMA for securitization financing. Jurisdictions with relatively lower sovereign credit risk profiles will be compelled to create rules that allow home country banks to treat sovereign currency as near risk-free, and regions with trading activity will undoubtedly face higher levels of non-modelable risk factors (NMRF) than the US or Europe.

The fact that FRTB implementation may have a relatively greater impact in jurisdictions with lower trading activity may well be one factor that jurisdictional regulators consider when they are setting their implementation rules.

There will be strong pressures driving regulators in different jurisdictions to create implementation rules that accommodate local idiosyncratic needs. As these differences are revealed, banks will inevitably seek ways to exploit even the subtlest variations between jurisdictions in their trading and banking activities. Regulators will need to be conscious of this trade-off when creating FRTB implementing legislation in their particular jurisdictions.

(iii) Disjointed approval processes: a hypothetical case study

The following hypothetical case study examines how the FRTB concept might be applied in practice across different jurisdictions, and the potential questions and conflicts that might arise.

Suppose that Big Global Bank (BGB) runs a UK RTD out of its London office, but at any one time it has clients around the globe requiring transactions or services in GBP sterling. Under the existing framework, BGB passes the sterling book from London to New York to Los Angeles to Singapore, with traders stationed in each location. This global book is then used to accommodate clients in 120 countries across the world.

How should BGB manage its sterling book under FRTB? Ideally, it would like to have a single sterling RTD stationed in London, with operating sub-desks in New York, Los Angeles, and Singapore. But that may not be possible under FRTB guidelines. Each of the jurisdictions in which BGB trades sterling (UK, US and Singapore) have rules that require risk governance, management, and capital regulation at the local level, thus each jurisdiction will require that BGB’s regional entity establish a separate RTD within that jurisdiction. Furthermore, BGB may need to establish new RTDs in the EU, Japan, Canada, and Australia to ensure they can service sterling clients in those regions.

Ultimately, the infrastructure costs of establishing multiple RTDs in different jurisdictions may make it uneconomic for BGB to fulfil all the sterling needs of its clients, particularly in smaller jurisdictions. As a result, regulators, especially in these smaller jurisdictions, may need to consider making allowances for operating sub-desks of RTDs to be outside their jurisdiction, as long as they have a clear line of sight on the credibility of the home country regulator.

Jurisdictional arbitrage

The BCBS acknowledged in early 2016 that national regulators will have differing ways of implementing the internal model approval (IMA) sections of the FRTB. These variances began to take shape during 2017, as rulemaking progressed at jurisdictional levels. For example, how should banks deal with the conflict that arises when a USD/SGD transaction takes place if the US supervisor allows IMA but the Singapore supervisor requires the standardised approach (SA)? FRTB gives no specific guidance on the issue other than to acknowledge its existence.

If national regulators do not enact bilateral agreements with other jurisdictions, it is likely that they will force their supervised banks to establish individual RTDs within national jurisdictions, even for globally traded instruments. Against this background, national regulators will need to be incentivized to establish as much multilateral cooperation as possible to avoid regulatory arbitrage across jurisdictions.

Local regulators may also need to consider other idiosyncratic factors that impact their specific jurisdiction. For example, the European Commission’s proposals for FRTB implementation, collectively known as CRR2, include several targeted deviations from the FRTB (e.g., in sovereign exposures, covered bonds, securitisations, trade finance and derogations for small and medium-sized banks) on top of the implementation differences mentioned earlier (e.g., phased timelines).

As individual jurisdictions begin to implement notices of proposed rulemaking within their regions, we can expect similar targeted deviations from the FRTB that will accommodate the specific requirements of individual markets. These targeted deviations will need to be weighed by the regulator against the need to maintain a harmonized global framework that minimizes regulatory arbitrage across jurisdictions.

New burdens for global co-ordination

There has been a broader trend in some jurisdictions to roll back globally imposed bank regulation—particularly of the kind represented by the BCBS Basel III standards and the FRTB—in favour of more bespoke regulation within specific jurisdictions.

One example is the US Financial Choice Act, which seeks to allow large, complex financial institutions to go bankrupt, repeals the concept of SIFIs, increases political oversight of the Federal Reserve System’s prudential and monetary authorities, and provides an “off-ramp” for Basel III capital and liquidity standards. Other examples include the European Commission’s November 2016 revisions to its CRR, which include deviations in the calculation of the Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) as well as the FRTB standards mentioned earlier.

Complexity of Global Supervision

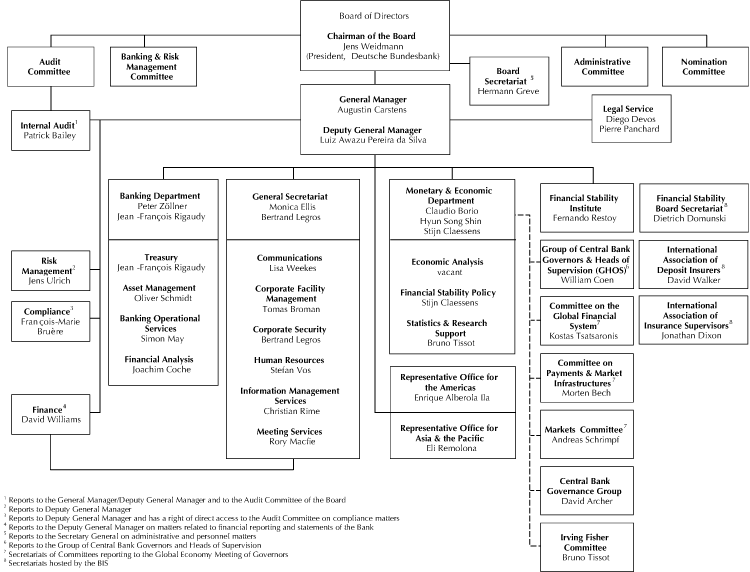

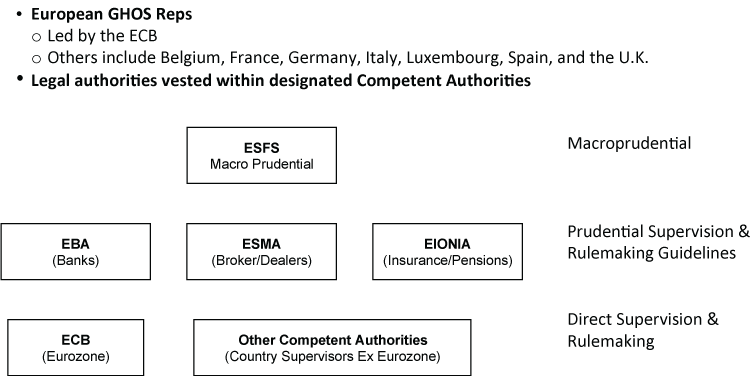

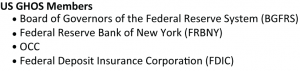

Compounding all of this is the complexity of regulatory bodies—not only at the global (BIS) level, but also within the regional jurisdictions that will need to create implementing regulation within their regions. The figures below illustrate this complexity for a sampling of larger jurisdictions.

Figure 1: Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Organization Framework

Figure 2: European Regulatory Framework

Figure 3: U.S. Regulatory Framework

Harmonization of supervisory standards is hard to achieve – for good reasons

In the end, jurisdictional differences in the implementation of FRTB and other Basel III standards will inevitably create risks of uncertainty and regulatory arbitrage. Global financial institutions will find it increasingly necessary to deconstruct global trading platforms into jurisdictionally independent groups, each subject to its own independent, capital, liquidity, risk management, and trading desk frameworks. Parent company capital, like water, will flow to the jurisdictions of least resistance and greatest return potential for the jurisdictionally agnostic parent company.

Ironically, small- and mid-sized institutions may find advantages in this model as jurisdictional “ring-fencing” could create a more level playing field for smaller institutions (which are confined to a single jurisdiction) to compete with larger, multinational institutions.

On the other hand, the challenges for supervisors and managements of large global financial institutions are clear. There are significant differences in both the architecture and mandates of different supervisory authorities around the globe. FRTB and Basel III in effect evolved as a response to the global financial crisis, but the differences between supervisors evolved globally over a much longer period.

In this light, it is not surprising that a harmonized supervisory response to the global financial crisis has been challenging. The crisis not only reshaped global regulatory standards, but also helped reshape many of the regulatory bodies, systems, and frameworks themselves—in ways that may make it even harder to implement the new rules in a harmonized way.